東西方文化習俗差異與禁忌:以暗黑觀光為例

研究暗黑觀光的議題確實可以通過流行文化追溯到民俗學,民俗學家多年來一直對死亡的文化方面保持興趣。

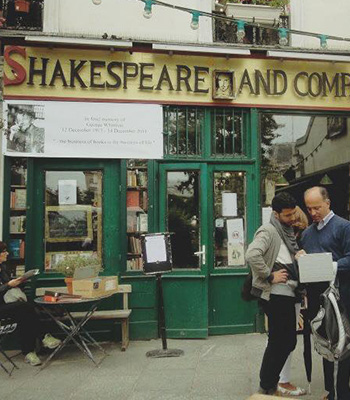

(Bennett&Round,1997)本文著重於文化方法和教育方法,很明顯看到「暗黑旅遊」一詞與教育有關,例如:達豪集中營紀念地。我親自訪問過四次以上,每次都有訪問的學校團體和許多國際觀光客。在幾乎所有的社會中,與死亡和紀念有關的習俗都是高度儀式化的,在這些社會中,存在著基於身體和靈魂的分離以及來世或輪迴的信仰體系,無論是否指定了屍體的「最終安息之所」。 (John Lennon&Malcolm Foley,2000)Sudnow(1967)和最近的Walter(1996)指出,在某些文化中,與包括硬件在內的過程的各個方面相關的業務在20世紀後期日益增長,導致死亡的「工業化」房地產、儀館甚至是服務的興起,其範圍已遍布全球。 (John Lennon&Malcolm Foley,2000)有人認為,通過流行文化中的死亡,無論是真實的還是虛構的,死亡已經成為全球通訊市場消費的商品。 (Palmer,1993)關於這些暗黑旅遊目的地的紀錄片和電視節目越來越多,並且在大多數情況下,暗黑旅遊強調的是當地文化現象,而不是討論暗黑旅遊的術語。這些爭論通常源於這樣的思想,即圍繞西方文化中「普通」情況下的死亡的儀式以某種方式已被「私有化」,即它們已不再只是死者親近的家屬、友人的事,而是屬於整個家族了。 (Lennon&Foley,2000年)

Indeed, death can be traced back through popular culture to folklore, in which folklorists have maintained an interest in the cultural aspects of death for many years. (Bennett & Round, 1997) This thesis focuses on the cultural approach and educational approach, it is rather obvious to see the term dark tourism is related to education, for example: Dachau concentration camps memorial site. Personally, visited more than four times, every time, there are school groups paying visits and many international tourists. Practices associated with death and remembrance are highly ritualized in almost all societies where there is a belief system based upon the separation of body and soul and afterlife or reincarnation, whether or not a ‘final resting place’ for the corporeal remains is designated. (John Lennon & Malcolm Foley, 2000) Sudnow (1967) and more recently Walter (1996) have pointed to the increasing ‘industrialization’ of death in the late twentieth century in some cultures where businesses associated with all aspects of a process that includes hardware, real estate and funeral or, even, cryogenic services have arisen, some global in their scope. (John Lennon & Malcolm Foley, 2000) Some have argued that, through its presentation, whether real or fictional, in popular culture, death has become a commodity for consumption in a global communications market. (Palmer, 1993) There is getting more and more documentaries and tv shows about these dark tourism destinations, and most of the time dark tourism is emphasized the local culture phenomenon instead of discussing the term of dark tourism. These arguments have often proceeded from the idea that the rituals surrounding death in ‘ordinary’ circumstances in Western cultures have somehow become ‘privatized’, i.e. that they have ceased to be a matter for immediate families and friends of the deceased or, more likely, the relatives of the deceased. (Lennon & Foley, 2000)

就全球新聞媒體而言,整個地球上的死亡都可以在西方世界的客廳中的電視裡被聽聞。 (Lennon&Foley,2000)媒體正在使前所未見方式讓以前不能被提及的禁忌廣為流傳;一張照片可以說成千上萬個名詞,包括其中的文化和教育形象。從這個意義上說,所有旅遊業都是文化旅遊業,因為如果不體驗其某些影響和文化產物,就幾乎不可能旅行到另一種文化。 (Richards,1995)因此,可以公平地說,本書提供的分析從根本上講是以歐洲為中心和「西方」的。在亞洲的某些地區,既可值得一提又可以被鼓勵的。 (Lennon&Foley,2000)在每個暗黑的旅遊目的地中,所有此類景點都必須有效,適當地進行開發、管理、解釋和宣傳。這些又需要對社會,文化,歷史和政治背景下的暗黑旅遊現像有更全面的了解。 (Sharpley&Stone,2009年)與許多暗黑的景點有關的一個問題是,開發、推廣或供遊客消費是否符合道德。例如,圍繞零地面觀景台的建設進行了激烈的辯論,使偶然甚至偷窺的遊客能夠與哀悼失去親人的人們並肩作戰(Lisle,2004年)。更廣泛地講,死亡商品化或商業化者的權利暗黑的旅行代表著值得考慮的重要的道德層面。 (Sharpley&Stone,2009)通常,渴望通過旅遊業獲利的企業或組織的營銷和促銷活動可能會增加此類網站的知名度。同樣,媒體經常在「宣傳」這些暗黑景點。 (Seaton,1996)媒體的作用一直是到死亡相關景點的旅遊業增長的中心,主要是通過增加謀殺和暴力死亡的地域特殊性,最近,通過全球傳播技術幾乎傳播事件當它們發生在世界各地的人們的家中時。 (Lennon和Foley,2000年)暗黑旅遊與其更廣泛的社會文化背景之間的關係仍然不清楚,儘管許多關鍵的實際問題和挑戰需要考慮。 ……如何在受更廣泛的社會文化影響的情況下訪問黑暗場所? (Sharpley&Stone,2009)在本論文的分析中將對此進行更詳細的討論。至於禁忌,在討論中也有很大的意義。它舉例說明了一些圍繞西方中心社會死亡率的基本問題,包括圍繞現代死亡率的明顯禁忌,以及在公共領域中面對和考慮這些「死亡禁忌」的必然方面。 (Sharpley&Stone,2009)

In the case of global news media, deaths across the entire planet can be consumed in the living rooms of the Western world. (Lennon & Foley, 2000) The media is making the before unseen, seen; the unspoken, spoken. A Photograph can speak thousands of words, including the cultural and educational image in it. In this sense all tourism is culture tourism as it is virtually impossible to travel to another culture without experiencing some of its effects and products. (Richards, 1995) Thus, it is fair to say that the analysis offered in this book is fundamentally Eurocentric and ‘Western’. Where remembrance is both possible and encouraged in some parts of Asia. (Lennon & Foley, 2000) In every dark tourism destination, all such sites or attractions require effective and appropriate development, management, interpretation and promotion. These in turn require a fuller understanding of the phenomenon of dark tourism within social, cultural, historical and political contexts. (Sharpley & Stone, 2009) One question relating to many dark sites and attractions is whether it is ethical to develop, promote or offer them for touristic consumption. For example, significant debate surrounded the construction of the viewing platform at Ground Zero, enabling casual or even voyeuristic visitors to stand alongside those mourning the loss of loved ones (Lisle, 2004) More generally, the rights of those whose death is commoditized or commercialized through dark tourism represent an important ethical dimension deserving consideration. (Sharpley & Stone, 2009) Frequently, the popularity of such sites may be enhanced by the marketing and promotional activity of businesses or organizations anxious to profit through tourism; equally, the media frequently play a role in ‘promoting’ dark sites. (Seaton, 1996) The role of the media has been central to this growth in tourism to sites and attractions associated with death, principally through increasing the geographical specificity of murder and violent death and, more recently, through global communication technology that transmits events almost as they happen into people’s homes around the world. (Lennon & Foley, 2000) The relationship between dark tourism and its wider socio-cultural context remains unclear, while a number of key practical issues and challenges require consideration. … How are visits to dark sites framed by wider socio-cultural influences? (Sharpley & Stone, 2009) It will be discussed more into details in the analysis on this thesis. As for the taboos, it also has a big dimension in the discussion. It exemplifies a number of fundamental issues that revolve around mortality within western-centric societies, including the apparent taboos that surround modern-day mortality, and the consequential aspects of confronting and contemplating these ‘death taboos’ in the public domain. (Sharpley & Stone, 2009)

因此,一旦死亡和對公共領域內死亡的討論曾經被視為禁忌(Mannino,1997; DeSpelder&Strickland,2002; Leming&Dickinson,2002),或者至少被宣佈為禁忌(Walter,1991),評論員就是現在挑戰死亡禁忌,探索死者與活人共享世界的環境。哈里森(2003)特別研究了死者如何被墓地、圖像、文學、建築和紀念碑吸收到生者的世界中。同樣,Lee(2002)回顧了現代人對死亡的迷戀,並得出結論,死亡正在重新回到社會意識中,這表明在不影響偏見的情況下剖析死亡的時機已經到來。他繼續主張死亡正在「從壁櫥裡出來,重新定義我們對生活的假設」(Lee,2004:155),從而打破了對死亡的現代沉默(和禁忌),死亡本身可能構成了一種防禦機制,個人反對他們不可避免的過世。顯然,死亡是一個超出日常意識的問題。當然,可以說,這種包圍過程導致對死亡的沉思成為禁忌。但是,如Mellor(1993)所述,包圍過程並不總是成功的。死亡曾經而且現在都是間接的,包括歷史,考古學,宗教,醫學,大眾傳媒和暗黑旅遊。 (Walter,2009)在亞洲,或者在台灣,關於暗黑旅遊的文獻很少。媒體並未傳達有關暗黑旅遊的正當想法,並且尚未被完全接受。在日本,活人與他們的祖先之間可能存在相互照料的關係:死者指導著活人,而活人則照顧死者。 (Walter,2009年)由於台灣文化受到日本文化的很大影響,因此在這方面,它們是相似的。一些當代西方死亡實踐的社會學家和人類學家(例如,Francis等,2005;情人,2008)表明,儘管在西方,沒有正式的宗教、儀式或語言可以讓活人照顧死者,儘管如此,例如通過宗教祭拜來做到這一點。西方墳墓的行為可能與日本家庭神社的行為沒有太大不同,他們與死者進行對話,傳遞來自死者世界的最新消息,詢問死者世界的生活並尋求指導。 (Walter,2009年)

Hence, where death and the discussion of death within the public realm was once considered taboo (Mannino, 1997; DeSpelder & Strickland, 2002; Leming & Dickinson, 2002), or at least proclaimed to be taboo (Walter, 1991), commentators are now challenging death taboos, exploring contexts where the dead share the world with the living. In particular, Harrison (2003) examines how the dead are absorbed into the living world by graves, images, literature, architecture and monument. Similarly, Lee (2002) reviews the disenchantment of death in modernity and concludes that death is making its way back into social consciousness, suggesting the time has come to dissect death without prejudice. He goes on to advocate that death is ‘coming out of the closet to redefine our assumptions of life’ (Lee, 2004: 155), thus breaking the modern silence (and taboo) on death which itself, perhaps, comprises a defense mechanism for individuals against their inevitable passing. Death is clearly one such issue to bracket out of everyday consciousness. It could be argued, of course, that this bracketing-out process has resulted in the contemplation of death becoming taboo; nevertheless, as Mellor (1993) notes, the bracketing process is not always successful. Death has been – and is – indirectly looked at include history, archaeology, religion, medicine, the mass media and dark tourism. (Walter, 2009) There are not many literatures about dark tourism in Asia, or more specifically in Taiwan; the media does not convey the righteous idea about dark tourism and it is not fully accepted yet. In Japan, there is the possibility of a mutual relationship of care between the living and their ancestors: the dead guide the living and the living care for the dead. (Walter, 2009) Since Taiwanese culture got influenced a lot by Japanese culture, in this aspect, they are similar. Some sociologists and anthropologists of contemporary western death practices (e.g.Francis et al., 2005; Valentine, 2008) have shown that, although in the West there is no formal religion, ritual or language by which the living may care for that dead, they nevertheless do this, for example by tending graves. Behavior at western graves may not be so dissimilar from that at Japanese household shrines, with conversations taking place with the dead, imparting the latest news from the world of the living, enquiring about life in the world of the dead and seeking guidance. (Walter, 2009)

就像媒體報導的災難一樣(Walter,2006),更具挑戰性的暗黑旅遊景點不僅挑戰個人,還挑戰文化。暗黑旅遊是我們文化的特定要素,就像宗教是許多文化中的特定要素一樣。然而,為了滿足遊客的情感需求,使人們能夠面對或思考死亡、使人了解悲劇或殘暴或記住親人,有必要對現場或事件進行解釋以認識到情感因素,或「將情感成分注入其主題」。 (Uzzell&Ballantyne,1998:154)。同時,還需要通過解釋來維持遺址或景點所紀念的人們的尊嚴。因此,對暗黑景點的解釋應盡可能呈現真實的敘述,以反映其情感內容。 (Sharpley&Stone,2009)一般來說,暗黑旅遊可被視為一種行為現象,它是由旅行者的動機而不是景點本身的特徵所定義的。 (Seaton 1996; Sharpley 2009)由於它被認為是一種行為現象,所以很有趣的是,旅行者在訪問暗黑旅遊目的地時會感受到不同的情感觀念。作為公墓,拉雪茲神廟擁有神聖的通常屬性,可以被視為異國情調(Foucault,1967),因為它「具有精神上的親近感和歸屬感」(Blom 2000:30)。

As with the media reporting of disaster (Walter, 2006), the more challenging dark tourism sites challenge not individuals, but culture. Dark tourism is a given element of our culture, just as religion is a given element of many cultures. Nevertheless, in order for the emotional needs of visitors to be satisfied, to enable people to confront or contemplate death, to make sense of tragedy or atrocity or to remember a loved one, there is a need for the interpretation of the site or event to recognize that emotional element, or to ‘inject an affective component into its subject matter’. (Uzzell & Ballantyne, 1998: 154). At the same time, the need also exists, through interpretation, to maintain the dignity of those people that the site or attraction commemorates. Thus, the interpretation of dark sites should, as far as possible, present an authentic narrative that reflects its emotive content. (Sharpley & Stone, 2009) Generally speaking, dark tourism may be considered as a behavioral phenomenon, defined by the traveler’s motives rather than the features of the attraction itself. (Seaton 1996; Sharpley 2009) Since it is considered as a behavioral phenomenon, it is interesting to know the different mindsets of the travelers’ emotions while they are visiting dark tourism destinations. As a cemetery, the Père-Lachaise possesses the usual properties of the sacred and may be considered as a heterotopia (Foucault, 1967), as it “offers a sense of mental proximity and feeling of belonging” (Blom 2000: 30)

圖/文/ Christina Tseng

攝影/ Websites

![設計獎項新訊|[小編精選]2026年3月份國際設計獎項資訊 DECO TV / 設計盒子](https://yusi-group.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/歐洲IADA2026_350.jpg)